Experiences with long-term underperformance in endurance athletes

An article written by Sophie Herzog, Øyvind Sandbakk, Trond Nystad and Rune Talsnes

Experiences with long-term underperformance in endurance athletes

Endurance sports impose high demands on athletes. Preparing for endurance events involves high training volumes and intensities and demand substantial mental resilience to deal with adversities and psychological pressure. Prolonged physical effort places stress on the cardiovascular, respiratory and muscular systems and is associated with high energy expenditure (maintaining adequate energy intake and proper hydration are vital). Furthermore, environmental conditions such as severe weather conditions (e.g., very high or low temperatures) or altitude can exacerbate physical stress and eventually lead to strain, i.e., internal stress/damage. Consequently, it comes as no surprise that most endurance athletes experience periods of underperformance throughout their careers. This phenomenon, characterized by a sustained drop in performance, can have various causes and manifest itself through numerous symptoms.

A recent study examined sex differences in self-reported causes, symptoms, and recovery strategies associated with long-term underperformance in a total of 82 (40 of which women) endurance athletes[i]. This is novel as most of the literature on non-functional overreaching (NFO)/overtraining syndrome (OTS) focuses on men, whereas the majority of the literature on relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs)[1] focuses on women. While underperformance is complex and always requires an individual and holistic approach, regardless of sex (as indicated by previous case studies[ii],[iii]), here, we will explore the findings of this recent publication and their implications for athletes and coaches.

Self-reported occurrence, symptoms and causes of underperformance

The first interesting take away of the study was that for both male and female athletes, the most frequent period of experiencing underperformance was between one and three months before the competitive period. This finding likely can be explained by the challenges encountered during the transition from the general to the specific preparatory period, where adjustments in training load and intensity distribution are common among endurance athletes. During this phase, often a progression from high volumes of low-intensity training to more high-intensity, competition-specific training takes place, combined with increased mental pressure and extensive travel for training camps and competitions. However, we believe that transition phases only become problematic if the previous period left the athlete strained and unable to adapt to the following training period. So, often the issues that arise during or after transition phases have roots in earlier training phases. A focus on longevity, continuity, regular systematic testing and proper intensity control systems throughout all phases of training can alleviate these problems. Altogether, the findings of this study, combined with our own experiences suggest that athletes and coaches should incorporate robust monitoring systems and always be aware of the load-recovery balance, especially during transition periods when training is intensified, to prevent maladaption and underperformance.

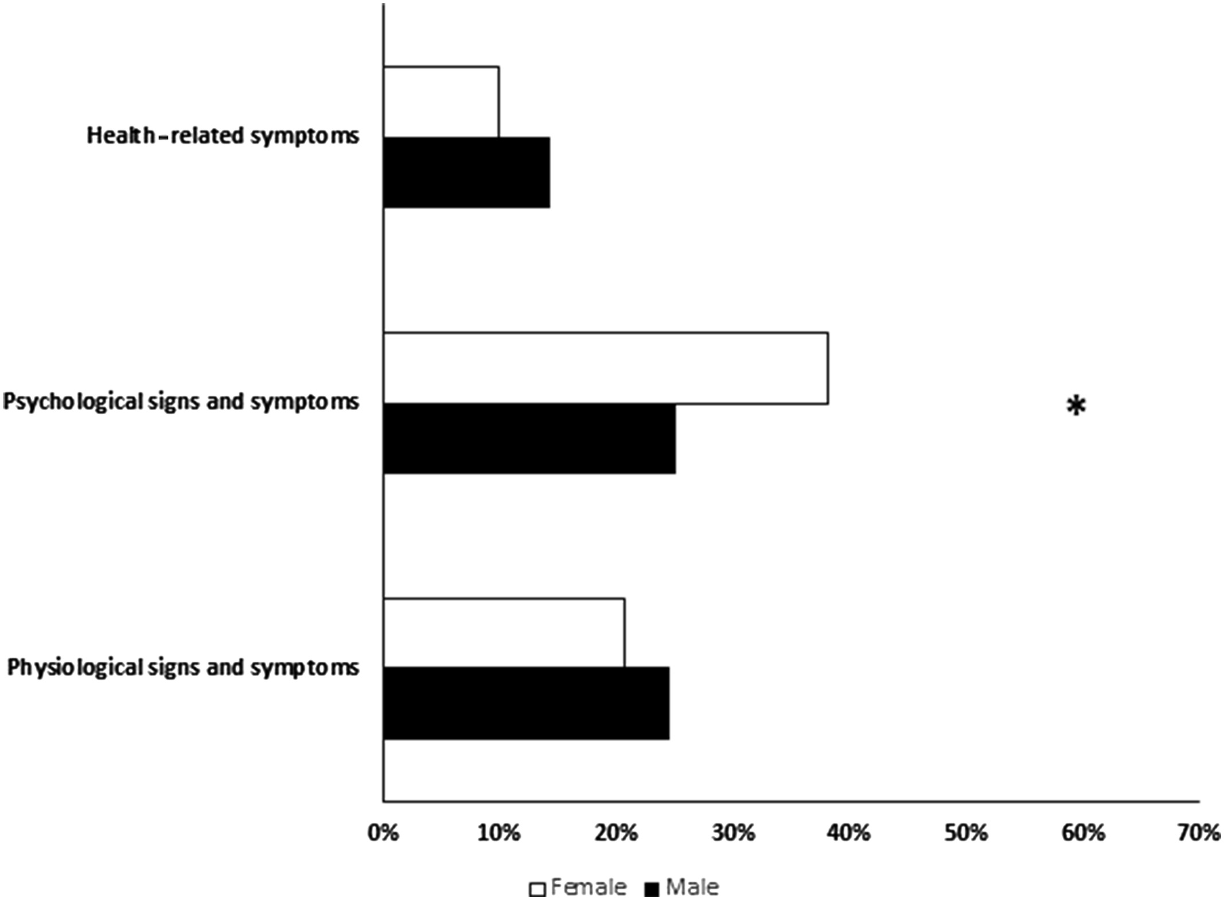

The most frequently self-reported symptoms associated with underperformance were psychological (31%), such as high perceived effort during sessions, feeling abnormally tired/fatigued or changes in mood state, followed by physiological (23%) symptoms such as performance decrements, changes in resting heart rate and heart rate variability and changes in physiological responses to exercise, followed by health-related (12%) symptoms such as increased incidence of illness, lack of menstruation/period or injuries. Interestingly, female athletes (38%) more often reported psychological symptoms versus males (25%).

Figure 1: Main categories of self-reported symptoms linked to underperformance in male and female endurance athletes. Figure from Agudo-Ortega et al., 2024.

The most common self-reported causes of underperformance were illness, mental/emotional challenges, training errors, lack of recovery, nutritional challenges or others. Females reported nutritional issues such as changes in body composition and body mass, often related to relative energy deficiency (REDs)/low energy availabiliy more commonly as causes of underperformance. Low energy states, occur when there is an imbalance between dietary intake and energy expenditure and these states can also be related with eating disorders (which can lead to various health and performance issues). Therefore, an increased awareness and individualized nutritional guidance, combined with psychological measures such as profiles of mood state (POMS) and questionnaires assessing low energy availability and disordered eating beahvior might be particularly relevant in female athletes, but could possibly be introduced as regular controls in training systems for both sexes. In contrast, male athletes frequently attributed their underperformance to specific training characteristics, such as rapid increase in training volume, muscle overload or too much high-intensity training. This points to a tendency, which seems especially pronounced among male athletes, to push beyond their limits, which can lead to burnout and performance decline. Recognizing these differing tendencies and motivations is crucial for developing effective recovery strategies, tailored to the needs of both male and female athletes.

Recovery Strategies: Different Paths to Rebound

The good news first: most (67%) athletes were able to recover from their state(s) of underperformance. However, interestingly, there was a tendency that more males (76%) recovered than females (58%), which could be related to the high propertion of psychological symptoms and nutritional challenges reported in females which might require longer to recover from. Generally, recovery from underperformance (especially for long-term states) is complex, and requires a tailored approach. Furthermore, recognizing and addressing the need for recovery can (and sometimes has to) be tackled on different levels. The study found that both sexes reported placing an increased emphasis on recovery, employing changes in the training process (e.g., load adjustments and better systems for monitoring load), getting mental/emotional support and professional guidance as well as nutritional interventions and improvements in the coach-athlete relationship. The only sex difference found in reported recovery strategies was that a higher proportion of male athletes indicated making changes to their training process as a primary recovery strategy. This could on one hand be due to correcting their potentially more “aggressive” training approaches or on the other hand one could also speculate that females are more hesitant to accept changes to their “normal” training routine and hence also have a slightly lower rate of recovery. However, it is important to note that although many athletes in this study reported recovering from their underperformance, other research indicates that many tend to end up in the same situation again[iv]. This suggests they may not have learned enough or acquired the right tools and systems to prevent recurrence, possibly also due to a lack of education and knowledge. This highlights the need for ongoing education, continuous improvement in training load management and associated methods, and the implementation of robust support systems to ensure long-term athlete well-being.

Genetic, cultural and societal Influences

The differences in how male and female athletes experience and recover from underperformance may partially also be attributed to cultural and societal factors. Historically, sports culture has emphasized physical toughness and endurance, traits often stereotypically associated with male athletes whereas discussing mental health issues can be seen as embarrassing or stigmatizing for men. Moreover, disordered eating behaviors are, despite a higher prevalence in female athletes, becoming increasingly apparent as well amongst men. In contrast, female athletes, who face unique challenges such as menstrual cycle impacts and societal pressures regarding body image, might be more attuned to the need for psychological and nutritional support. However, every athlete, regardless of gender, tends to have certain extreme behaviors or tendencies. This highlights the need for a supportive environment that recognizes, understands and caters to the specific needs of athletes and encourages open discussions about both physical and mental health.

Practical application

Generally, it can be said that a holistic approach to recovery is essential, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of underperformance and the need for comprehensive support systems. For coaches and athletes in endurance sports, this can be summarized into several key takeaways:

Prevention

Tailored Training Programs and support structures: Coaches should develop training programs that consider the different causes and symptoms of underperformance in male and female athletes. This includes fostering a supportive environment, such as psychological support or nutritional guidance.

Monitoring: Regular monitoring of both physical and psychological indicators can help avoid a state of underperformance as well as early detection of underperformance. Utilizing training diaries and technologies to track the balance between training load and recovery and using them to adjust the training plan can prevent the escalation of issues and promote timely intervention.

Communication: Maintaining a close and continuous dialogue between coaches, athletes, nutritionists, psychologists and medical staff is essential. This collaborative approach ensures that all aspects of an athlete’s health and performance are monitored and addressed promptly.

Nutrition and recovery: Emphasizing proper nutrition and recovery strategies is crucial. Coaches and athletes should be aware of the demands of their sport and work with nutritionists to ensure that the nutritional intake is sufficient to support the training requirements. Recovery should be seen as an “active ingredient” and can be strategically implemented as part of the training process and planning.

Intervention:

Comprehensive Recovery Plans: Recovery strategies should be individualized based on initial and ongoing risk assessments, addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of underperformance. An adequate recovery period can enhance recovery outcomes and support long-term athlete well-being.

Professional guidance: A systematic and holistic approach, for example by engaging a professional multidisciplinary team can provide the necessary support and expertise to address complex underperformance issues and helps athletes to build trust and gain knowledge throughout their (recovery) process.

Long-term strategies:

Education and awareness: Educating athletes and coaches about the signs of underperformance, including potential causes and symptoms, can foster a proactive culture that prioritizes well-being and long-term development.

Flexible training plans: Being adaptable with training planning and adjusting loads, especially during high-risk periods such as the transition from general to specific preparatory phases or in other high-stress situations/environments, can prevent an over-accumulation of stress and reduce the risk of underperformance.

Understanding burnout, unexplained states of maladaptation and performance decline in endurance sports is crucial, yet there is still a significant gap in research, particularly concerning sex differences. While it is essential to develop effective prevention and recovery strategies for underperformance across the board, exploring potential sex and demographic differences in the causes and symptoms of underperformance in endurance athletes is equally important. Although this paper provides initial insights into potential sex-related disparities, the most critical take away is that individual differences exist regardless of gender. By acknowledging these differences and adopting a tailored, holistic approach, coaches and athletes can better navigate the complexities of long-term underperformance and achieve sustained success in endurance sports.

Broader implications for burnout patients in high-ambition professionals

The findings and practical applications discussed in this article are probably not only relevant to endurance athletes but can also be applied to other high-ambition professionals, such as coaches and other leaders who often face similar challenges related to load (mis-)management, stress, psychological pressure and eventually burnout or underperformance. High expectations and the pressure to perform can lead to mental and physical strain, similar to that experienced by athletes. Therefore, the strategies for preventing and recovering from underperformance in athletes – such as tailored training programs, regular monitoring, effective communications, proper nutrition and recovery routines – are equally applicable to preventing and managing burnout in high-ambition professionals. Creating a supportive environment that encourages open discussions about mental and physical health, providing ongoing education, and implementing flexible plans to adjust workload and stress levels (instead of cultivating a workaholic-glorifying culture) can help these individuals achieve sustained performance, development and well-being in their demanding roles as well as living a more balanced and happy life. This holistic approach underscores the universal need for balanced load management, psychological support and proactive health strategies in any high-stress, high-performance context.

Need Help Navigating Underperformance?

At MYRA, we understand the complexities of long-term underperformance and burnout - whether you're an athlete, coach, or high-ambition professional. Our mission is to empower you with the tools, knowledge, and support you need to overcome setbacks and achieve sustainable performance.

If you’re struggling to find your way back to peak performance or want to prevent underperformance before it starts, reach out to us. We’re here to help you build a resilient foundation for long-term success and well-being.

References

[1] REDs as well as NFOR/OTS can be subcategories of the umbrella term “underperformance”, covering somewhat related but different and often unexplained states of maladaptation and performance decline.

[i] Agudo-Ortega A, Talsnes RK, Eid H, Sandbakk Ø, Solli GS. Sex Differences in Self-Reported Causes, Symptoms, and Recovery Strategies Associated With Underperformance in Endurance Athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2024 Jun 11:1-9. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2024-0131. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38862109.

[ii] Solli GS, Tønnessen E, Sandbakk Ø. The Multidisciplinary Process Leading to Return From Underperformance and Sustainable Success in the World's Best Cross-Country Skier. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020 May 1;15(5):663-670. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0608. PMID: 32000138.

[iii] Talsnes RK, Moxnes EF, Nystad T, Sandbakk Ø. The return from underperformance to sustainable world-class level: A case study of a male cross-country skier. Front Physiol. 2023 Jan 9;13:1089867. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.1089867. PMID: 36699686; PMCID: PMC9870290.

[iv] Raglin, J. S. (1993). Overtraining and staleness: Psychometric monitoring of endurance athletes. In

R. N. Singer, M. Murphey, & L. K. Tennant (Eds.), Handbook of research on sport psychology (pp. 840-850). New York: Macmillan.